CYRUS KABIRU

Artist Room

Artist Room

26.09.20 – 24.10.20

Nairobi, Kenya

Artist Rooms is a new feature of SMAC Gallery’s exhibition programme. Created in response to art fairs and exhibitions being postponed globally as a result of the global Covid-19 pandemic, Artist Rooms creates a space of experimentation and easier work flow to accommodate for these restrictions.

Text by Amogelang Maledu

The Msanii giving trash a second chance: Cosmopolitan contamination in Cyrus Kabiru’s work

‘’You can’t say my work is ‘African’ because I mix trash from different places in the world’’.

Cyrus Kabiru

Globalisation, in its interconnectivity, is also the reason why we are currently affected by a global health pandemic. That; and a generally decaying Earth, devastating not just the cycle of nature and its multiple ecosystems, but similarly devastating and widening the fissures of socio-political and economic inequalities all over the world. Even though there have been these ethical dilemmas of human progress in relation to the Machine Age and intersectional justice, the relevance of these topical discussions is especially highlighted by the artworks produced by visual artist, Cyrus Kabiru, and the concerns in his art practice. Through his candid revelation ‘’I give trash a second chance’’; and accounting to the deprivation of leisurely objects (like sunglasses, bicycles and toys) growing up in the townships of Nairobi, Kenya – it is easy to see why Kabiru’s practice is operative outside of the art world’s value laden emphasis of creativity and autonomous experimentation. Kabiru is instead more interested in gestures of sustainable socio-economic and environmental survival. He tells me this while accounting to how, whenever he travels to various countries in the world to showcase his work, he always travels with an empty suitcase awaiting to be filled with discarded trash from all over the world, that he later transforms into art.

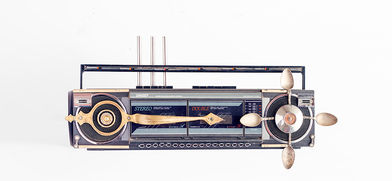

Kabiru makes art which, in its contemporaneity, is what philosopher Kwame Anthony Appiah would call ‘cosmopolitan contamination’. These cosmopolitan inferences also indicate a localization in their international origins, often revealing the cracks of cultural or hegemonic purity through the agency of those who choose to repurpose and appropriate its cultural significance for various contexts or uses. In taarifa kamili – ‘comprehensive news’ (2020), Kabiru investigates the impact and content of analogue radios and bicycles in Nairobi -objects that were both important in his youth and in sparking his creative muscle. Growing up, Kabiru’s father used to be a bicycle hawker and often he would task Kabiru with cleaning his bicycle after some hawking in the winding slump roads of Nairobi filled with sewage: Kabiru hated this chore. However, this childhood irritant is where he learned how to dismantle bicycles and reassemble them, later creating his own bicycles that he desired.

Looking at Kabiru’s eccentric and colourful latest body of work: radios and bicycles made entirely out of discarded found objects from all over the world, illustrates his ingenuities: artistic finesse and the self-imposed responsibility of artistic shifts concerned with modernity’s accumulated waste and pollution. It is appropriate to speak to Kabiru’s practice (borrowing from cultural critic Nikos Papastergiadis) as a radical task that starts with the utopia of creating something new and unique with the dystopia that currently surrounds urban life. Kabiru, in his particular concerns of creating ubiquitous objects attached to his memories as a youth, explores the topographies and ebbs of modernization through the aesthetics of excavated trash and reinvention to deal with the legacies of modernity’s refuse.

It is important for Kabiru to explicitly reveal, in the opening line of this text, that his work must not be laced with static Conradian understandings of African art. Instead, his work gestures to aesthetics of dynamism found within not just Nairobi where he grew up, but all over the world where he is often travelling for exhibitions, workshops and residencies. In fact, his practice contemplates – now more than ever where the movement of people and things has been restricted – the layered ‘’social lives’’ of things, their multiplicity, convergence and movements in our daily lives. What do these excavated objects, which Kabiru uncovers and transforms into sculptural artworks, say about the futurity of the postindustrial landscape? It is from these questions that Kabiru’s work is globally relevant, sifting through the importance of artistic and cultural reconversion, rethinking and reimagining in moments of crisis and dystopian decays. How and what can art tangibly contribute to these topical issues?

I think some answers can be found in the inconvenience of how a global pandemic affected Kabiru’s exhibition, presented by SMAC Gallery and initially scheduled to open in Cape Town. However, the pandemic presented a health, safety and even political process of negation where the exhibition is showing in Thika Ngoigwa, Kenya. This is revelatory in positively shifting and decentring the commercial urbanity of typical art world centres. Kabiru’s solo exhibition taarifa kamili – ‘comprehensive news’ unintentionally being exhibited at Art Orodha in Thika Ngoigwa is a necessary symbolic event in revealing the limitations of the perpetual socio-political hierarchies of the art world.

Text by Amogelang Maledu